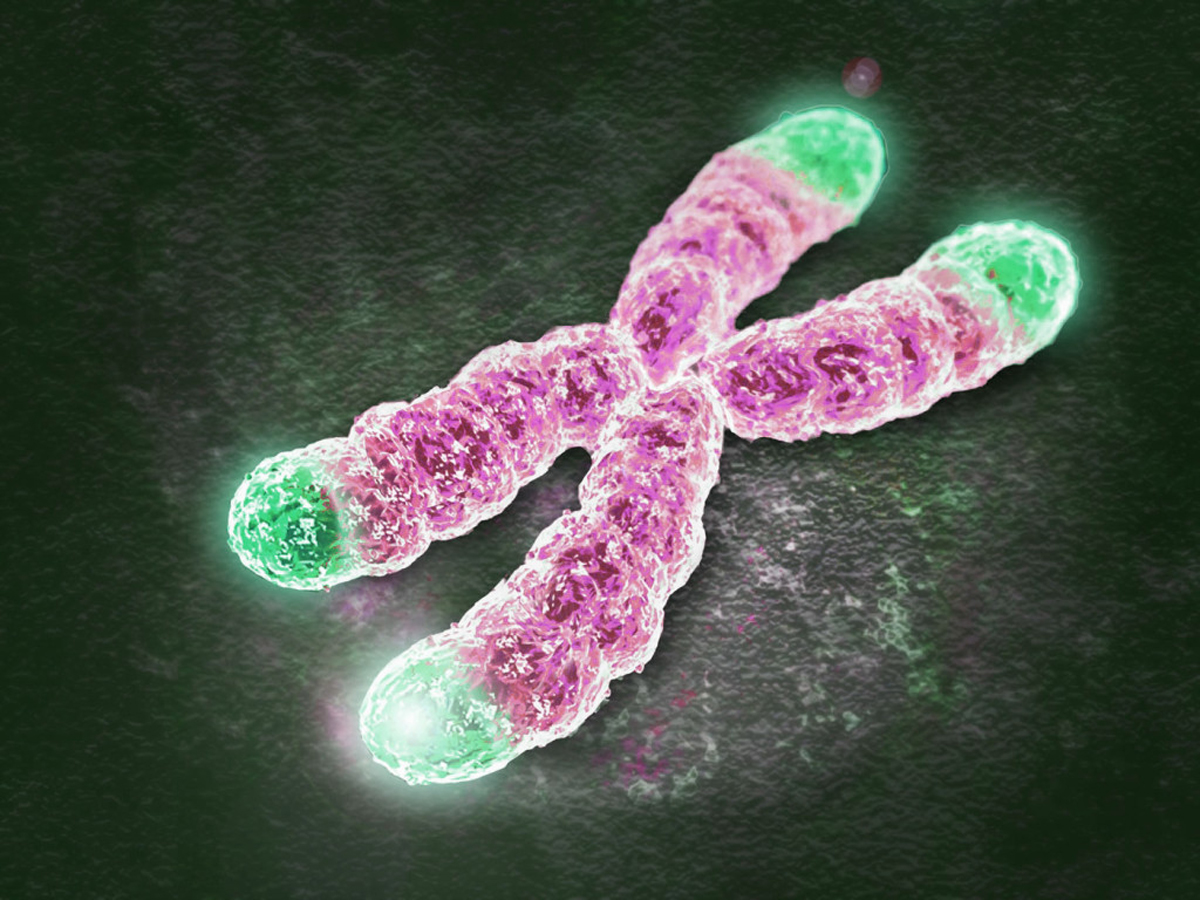

Telomeres are natural protectors of our DNA, acting like caps at the ends of chromosomes so they don’t deteriorate or fuse with other chromosomes. The destruction or deformation of our chromosomes is what causes genetic problems at birth like Down’s syndrome and aging problems like cancer, osteoporosis, and dementia. Telomeres are much like the plastic tips at the ends of shoelaces – and much like those tips, they become chipped and expose the shoelace (DNA) depending how much wear-and-tear they withstand.

Keeping with this shoelace analogy, the less trauma these plastic tips endure, the longer they last and the longer the shoelaces remain intact. They also work better by being able to be threaded through the shoelace holes. When telomeres break down, the genes become less reliable in their functions, and their dysfunction is what is happening at the cellular level when we age. By the time we feel the effects of aging, our cells are far from what they used to be.

So how do we maintain telomeres and keep them from breaking down? In other words, how do we slow the effects of aging at the cellular level? One obvious to-do is to avoid stress; stress can cause damage at the cellular level, re-programming genetic material to behave in ways they’re not meant to. Another obvious to-do is to exercise, not the high-impact physical stress exercise (which can cause more damage), but gentle exercise like yoga or brisk walking that encourage deep breathing and can restore cells. Another major cell restoration factor is nutrition; feeding living cells with living food. The final component for protecting cells is by maintaining relationships that are healing and not stressful; social stability eventually leads to cell stability.